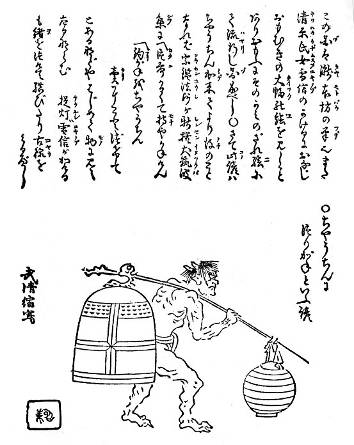

提灯に釣鐘

Chochin ni Tsurigane A Paper Lantern

and a Temple Bell

鐘ねもちやうちんよりはかろがろと

はやく出来よと云わぬばかりぞ

It’s as

though he’s saying, “Quickly get to where you can lift a temple

bell more easily than a paper lantern!”

「提灯釣鐘」は古い諺で「釣り合いがとれぬこと」をいう。もっとも早いところでは、『犬筑波集』に、

片荷かろくて持(もち)やかねけん

つり鐘をちやうちん売(うり)に言伝(ことづて)て

漁翁が針やあぐる山寺

つりがねを鉤(つりばり)にとりなす提灯うり山寺へ行くべし

とある。前半は、(提灯をひとつ持った)釣鐘売りに、釣鐘を(山寺に届けてくれ)と、ちょっとことづけたのだが、天秤棒でかつぐには、片荷になって、さぞ扱いにくいことだろう、という意。

後半は、その釣鐘を釣針のように軽々とあつかってしまう提灯売りならば、山寺にゆくがよい、というこころ。不釣り合いなどは、突破してしまうところである。

また『瓦礫雑考』には次のようにある。

この図は瀧本坊の筆なり。また、清原氏女雪信のかけるにおなじおもむきの大幅の絵を見しことあり。おもふ

この図は瀧本坊の筆なり。また、清原氏女雪信のかけるにおなじおもむきの大幅の絵を見しことあり。おもふ

に、そのかみのざれ絵にて流行(はやり)し図成べし。さて、この諺はちやうちん出来てより後のことなれば、

宗鑑法師が新撰犬筑波集に、

片荷かるくて持ちやかねけん

釣がねをちやうちん売にことづけて

とあるなぞやはじめて物に見へたるならむ。提灯は雪信がかけるも緒をつけて結びたり。古様をしるべし。

白隠のいうところも、『新撰犬筑波集』の後段に同じことで、不釣り合いなどは突破して、釣鐘を提灯よりも軽々と持て、というこころ。

『於仁安佐美』巻之上、11丁表に、

怱然トシテ漆桶ヲ打破シ了ツテ、大イニ歡喜シ大イニ踊躍シ、佛祖ヲ並呑シ諸方ヲ罵詈シ、燈籠躍ツテ露柱ニ

入リ、佛殿走ツテ山門ヲ出ヅ、人ハ橋上ヨリ過レバ、橋ハ流テ水ハ流レズ、何ンノ難キ事カ是レアラン。華嚴

ノ四種ノ法界、法華ノ唯有一乘、今掌上ヲ見ルガ如シ。

とあるが、「人ハ橋上ヨリ過レバ、橋ハ流テ水ハ流レズ」という境界でもあろう。

「提灯釣鐘」は、大津絵の画題にもなっていて、そこでは猿が提灯と釣鐘を担う絵柄になっている。また、享保10年の『狂歌仙』には下のような図も載っている。ここでのココロは「片思い」(=片重い)というところだが、いま白隠の例とはかかわりはない。

The painting

shows Hotei (Hakuin)

carrying a paper lantern and a temple bell on a shoulder pole, with the heavy

bronze bell apparently lighter than the lantern. This image of shouldering a

temple bell and paper lantern was a common one at the time. For example, the Shinsen Inu Tsukuba Sh¨ 新撰犬筑波集, a humorous work published

in 1539, has the following passage:

片荷かろくて持(もち)やかねけん

つり鐘をちやうちん売(うり)に言伝(ことづて)て

漁翁が針やあぐる山寺

つりがねを鉤(つりばり)にとりなす提灯うり山寺へ行くべし

The basic meaning of the

first and second lines is that a lantern seller, asked to bring a bronze bell

to a mountain temple, attaches it to his shoulder pole opposite his one unsold

lantern. The unbalanced weight makes the load hard to bear, of course, and the

lantern seller, in the third and fourth lines, wishes that he could turn the

bell (鐘 tsurigane) into a

hook (鉤 tsuribari) while he

carries it to the mountain temple. There is, of course, a play on the

words tsurigane and tsuribari.

The basic meaning of the

first and second lines is that a lantern seller, asked to bring a bronze bell

to a mountain temple, attaches it to his shoulder pole opposite his one unsold

lantern. The unbalanced weight makes the load hard to bear, of course, and the

lantern seller, in the third and fourth lines, wishes that he could turn the

bell (鐘 tsurigane) into a

hook (鉤 tsuribari) while he

carries it to the mountain temple. There is, of course, a play on the

words tsurigane and tsuribari.

Hotei’s

comment, “Quickly get to where you can lift a temple bell more easily

than a paper lantern,” brings to mind many similarly paradoxical Zen

statements, such as, “Empty-handed, yet holding a hoe; walking, yet

riding a water buffalo. Someone crosses a bridge; the bridge flows, but the

water flows not” (Fu Daishi; C. Fu Dashi 傅大士, 497–569). These

express the transcendence of the relative world of duality, the world of self

and other.

The image of a shoulder pole loaded with

a temple bell and paper lantern also played on the word kataomoi, which can mean either

“heavy on one side” (kataomoi 片重い) or “unrequited love” (kataomoi 片思い, lit., “one-sided

affection”). Prints exist from the time of Hakuin

showing a man carrying a shoulder-pole loaded in this way, and gazing longingly

at a pretty woman walking beside him. (芳澤勝弘+Thomas

Kirchner)